Introduction

Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic lunar calendar, occupies a central and deeply revered position in the life of Muslims around the world. It is a sacred period marked by fasting from dawn to sunset, heightened spiritual awareness, ethical self-discipline, and an intensified sense of community. Closely intertwined with the daily fast is Iftar, the evening meal that breaks the fast at sunset, which is not merely a moment of physical nourishment but also a ritual imbued with profound religious, social, and cultural meaning.

This article offers a comprehensive and professionally grounded exploration of Ramadan and Iftar within Islam. It examines their theological foundations, historical development, ritual practices, spiritual objectives, social dimensions, and contemporary expressions across diverse Muslim societies. By integrating religious doctrine with lived experience, this discussion aims to present Ramadan and Iftar as a holistic system of worship that harmonizes body, mind, and soul, while fostering empathy, generosity, and global interconnectedness.

1. The Meaning and Origins of Ramadan

1.1 Linguistic and Conceptual Significance

The word Ramadan (رمضان) derives from the Arabic root “ramida” or “ar-ramad,” meaning scorching heat or dryness. Classical Islamic scholars interpret this metaphorically, suggesting that Ramadan “burns away” sins through acts of worship, repentance, and moral discipline. The name reflects both physical restraint and spiritual purification.

Ramadan is not simply a month of abstention from food and drink; it is a time dedicated to reorienting the believer’s life toward God (Allah), strengthening consciousness of divine presence (taqwa), and cultivating ethical excellence.

1.2 Ramadan in the Islamic Calendar

Islam follows a lunar calendar consisting of twelve months, each beginning with the sighting of the new crescent moon. As a result, Ramadan shifts approximately 10–11 days earlier each solar year, cycling through all seasons over a 33-year period.

The beginning and end of Ramadan are traditionally confirmed by moon sighting, a practice that reinforces communal participation and adherence to prophetic tradition (Sunnah). In modern contexts, astronomical calculations are also used in many countries, sometimes leading to variations in start dates across regions.

2. The Religious Foundations of Fasting (Sawm)

2.1 Fasting as a Pillar of Islam

Fasting during Ramadan (Sawm) is one of the Five Pillars of Islam, the core acts of worship that structure a Muslim’s faith and practice. The obligation is established in the Qur’an:

“O you who believe! Fasting is prescribed for you as it was prescribed for those before you, so that you may attain God-consciousness (taqwa).”

(Qur’an 2:183)

This verse highlights that fasting is not unique to Islam but part of a broader Abrahamic tradition, while emphasizing its ultimate purpose: the cultivation of taqwa.

2.2 Who Is Required to Fast

Fasting is obligatory for all adult, sane Muslims who are physically able to do so. However, Islamic law (Sharia) provides compassionate exemptions, including:

- The sick or chronically ill

- Travelers

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women (if fasting poses harm)

- The elderly and physically incapable

- Women during menstruation or postnatal bleeding

Missed fasts may be made up later (qada’) or compensated through charitable acts (fidya), reflecting Islam’s balance between obligation and mercy.

2.3 What the Fast Entails

From dawn (Fajr) until sunset (Maghrib), Muslims abstain from:

- Food and drink

- Smoking

- Sexual relations

Equally important, fasting includes restraint from immoral behavior such as lying, gossip, anger, and injustice. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ emphasized that fasting without ethical conduct diminishes its spiritual value, underscoring that Ramadan is a comprehensive moral discipline.

3. Spiritual Dimensions of Ramadan

3.1 Taqwa: God-Consciousness

The primary spiritual objective of Ramadan is the development of taqwa, a state of heightened awareness of God that guides moral decision-making. Hunger and thirst serve as reminders of human dependence on divine provision, fostering humility and gratitude.

3.2 Increased Worship and the Qur’an

Ramadan is known as the “Month of the Qur’an”, commemorating the revelation of the first verses to Prophet Muhammad ﷺ:

“The month of Ramadan in which was revealed the Qur’an, a guidance for mankind…”

(Qur’an 2:185)

Muslims are encouraged to:

- Recite and study the Qur’an

- Perform additional nightly prayers (Taraweeh)

- Engage in supplication (du‘a’) and remembrance (dhikr)

- Seek forgiveness and spiritual renewal

3.3 Laylat al-Qadr: The Night of Power

One of the most significant moments of Ramadan is Laylat al-Qadr, believed to occur during the last ten nights, most commonly on the 27th night. The Qur’an describes it as:

“Better than a thousand months.” (Qur’an 97:3)

Worship on this night is believed to yield immense spiritual reward, making it a focal point of devotion and reflection.

4. Iftar: Breaking the Fast

4.1 Definition and Religious Significance

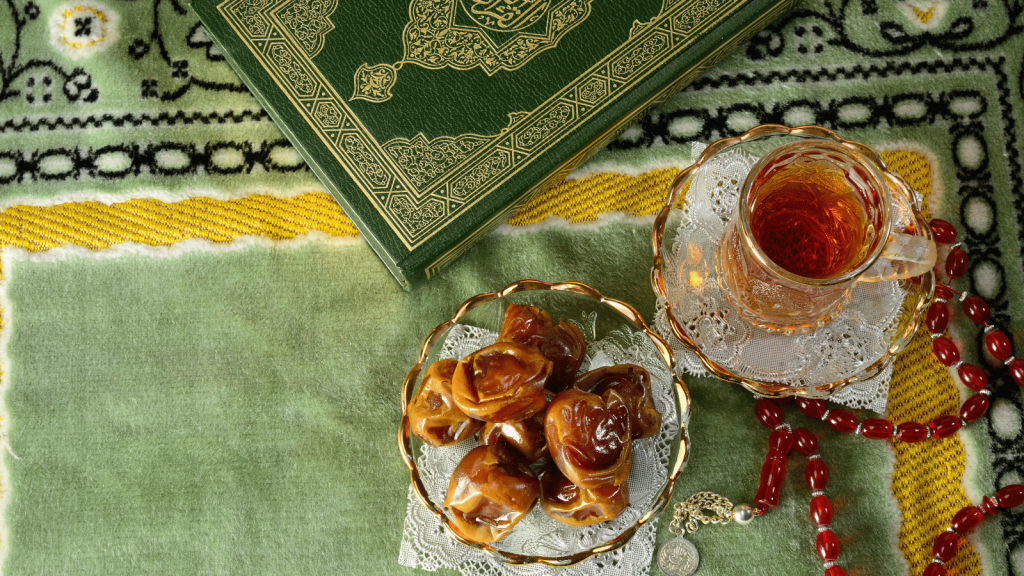

Iftar refers to the meal with which Muslims break their daily fast at sunset. While it is a physical necessity, it also holds strong religious symbolism. The Prophet Muhammad ﷺ traditionally broke his fast with dates and water, a practice widely followed today.

A common supplication at Iftar expresses gratitude and fulfillment:

“O Allah, for You I have fasted, and with Your provision I break my fast.”

4.2 Timing and Ritual Structure

Iftar begins immediately after sunset, signaled by the call to the Maghrib prayer (adhan). Many Muslims follow a two-stage structure:

- Initial break – Dates and water

- Prayer – Performing Maghrib

- Main meal – A more substantial dinner

This structure reflects balance between worship and nourishment.

5. Culinary Traditions of Iftar Across Cultures

One of the most visible and diverse expressions of Ramadan is the Iftar table, which varies widely across regions while retaining shared symbolic elements.

5.1 Common Elements

Despite cultural differences, many Iftar meals include:

- Dates (symbolizing prophetic tradition)

- Water or milk

- Soup (for gentle nourishment after fasting)

- Bread or grains

- Fruits and sweets

5.2 Regional Variations

- Middle East: Lentil soup, hummus, falafel, grilled meats

- South Asia: Samosas, pakoras, fruit chaat, sweet drinks

- Turkey: Pide bread, olives, cheese, güllaç dessert

- North Africa: Harira soup, couscous, dates

- Southeast Asia: Rice dishes, coconut-based desserts

These cuisines reflect local agricultural resources and culinary heritage while reinforcing communal identity.

6. Social and Communal Dimensions of Iftar

6.1 Family and Community Bonding

Iftar is often shared with family members, reinforcing kinship ties. In many communities, mosques and charitable organizations host public Iftar gatherings, welcoming the poor, travelers, and even non-Muslims.

6.2 Charity and Social Responsibility

Ramadan places strong emphasis on charity (Zakat and Sadaqah). Providing food for fasting individuals is considered highly meritorious. Many Muslims sponsor Iftar meals, donate to food banks, and support humanitarian causes, embodying the social ethics of Islam.

6.3 Interfaith and Cross-Cultural Engagement

In multicultural societies, Iftar has become a platform for interfaith dialogue, where people of different backgrounds are invited to share the meal. Such events promote mutual understanding and counter stereotypes by highlighting hospitality and shared human values.

7. Health, Balance, and Moderation

7.1 Physical Considerations

When observed properly, fasting can encourage:

- Improved self-control in eating

- Mindful nutrition

- Detoxification and metabolic balance

However, Islam discourages excess. Overindulgence at Iftar contradicts the ethical spirit of Ramadan, which advocates moderation and gratitude.

7.2 Psychological and Emotional Well-being

Ramadan fosters emotional resilience, patience, and empathy for those who experience hunger daily. The structured routine of fasting, prayer, and community engagement often contributes to mental clarity and inner peace.

8. Ramadan and Iftar in the Modern World

8.1 Urban Life and Work Schedules

In contemporary societies, Muslims balance fasting with demanding work and academic schedules. Flexible hours, remote work, and institutional accommodations increasingly reflect recognition of religious diversity.

8.2 Media, Technology, and Global Connectivity

Digital platforms now play a significant role in Ramadan:

- Live-streamed prayers

- Online Qur’an study groups

- Charity campaigns through social media

- Virtual Iftar gatherings

These developments illustrate how traditional practices adapt to modern realities while preserving their essence.

9. The Ethical Message of Ramadan and Iftar

Beyond ritual observance, Ramadan conveys a universal ethical message:

- Self-discipline over desire

- Compassion over indifference

- Generosity over greed

- Community over isolation

Iftar, as the daily culmination of fasting, symbolizes reward after patience and the joy of shared sustenance, reminding believers that true fulfillment lies in gratitude and service.

Conclusion

Ramadan and Iftar together form a profound spiritual, social, and ethical system within Islam. Ramadan disciplines the self through fasting, prayer, and reflection, while Iftar restores the body and strengthens communal bonds through shared nourishment and generosity. Rooted in divine revelation yet expressed through diverse cultural forms, these practices embody Islam’s holistic vision of human well-being.

In an increasingly fragmented world, the values cultivated during Ramadan—empathy, restraint, gratitude, and solidarity—resonate far beyond the Muslim community. Iftar tables around the globe, whether modest or elaborate, stand as quiet but powerful symbols of unity, reminding humanity that spiritual growth and social harmony begin with mindful restraint and shared bread.